The Ph.D. Grind

meme

meme

From talking with other professors and senior Ph.D. students in my department, I realized it was the norm for new students to join an existing grant-funded research project rather than to try creating their own original project right away.

During almost waking moment, I was either working, thinking about work, or agonizing over how I was stuck on obscure technical problems at work. Unlike a regular nine-to-five job(e.g., my summer internships) where I could leave my work at the office and chill every night in front of television, research was emotionally and mentally all-consuming. I found it almost impossible to shut off my brain and relax in the evenings, which I later discovered was a common ailment afflicting Ph.D. students.

However, the problem with dreaming up ideas in a vacuum back then was that I lacked the experience necessary to turn those ideas into real research projects. Having full intellectual freedom was actually a curse, since I was not yet prepared to handle it.

Contrary to romanticized notions of a lone scholar sitting outside sipping a latte and doodling on blank sheets of notebook paper, real research is never done in a vacuum.

Be proactive in talking with professors to find research topics that are mutually interesting, and no matter what, don’t just hole up in isolation.

There are two sources of doubt: I don’t trust their interpretation of the measures, and they don’t use very effective statistical techniques.” In the cutthroat world of academic publishing, simply being passionate about a topic is nowhere near sufficient for success; one must be well-versed in the preferences of senior colleagues in a particular subfield who are serving as paper reviewers.

Unlike our peers with regular nine-to-five jobs, there was no immediate pressure for grad students to produce anything tangible—no short-term deadlines to meet or middle managers to please. For most students in my department, nobody would notice or care if they took one day off, so by extension, why not take two days off, a whole week off, or even a whole month off? Therefore, it’s unsurprising that many Ph.D. students who drop out do so around their third year.

I tried to “micromanage” myself by setting small, bite-sized goals and attacking them every day, hoping that positive results would eventually come. But it was hard to keep myself motivated when I didn’t see noticeable daily progress.

Many projects last longer than individual Ph.D. student “lifetimes.” But as long as the original vision is realized and published, then the project is considered a success. The professor is happy, the university department is happy, the grant funding agency is happy, and the final surviving set of students is happy. But what about the student casualties along the way? A tenured professor can survive several years’ worth of failures, but a Ph.D. student’s fledgling career—and psychological health—will likely be ruined by such a chain of disappointments.

From this experience, I learned about the importance of being endorsed by an influential person; simply doing good work isn’t enough to get noticed in a hyper-competitive field.

Although daily check-ups could potentially be stressful, I actually found them immensely helpful since Tom wasn’t intimidating or judgmental at all. Getting immediate daily feedback made it easy for me to stay focused and motivated.

I wish I could say that my solo brainstorming sessions were motivated by a true love for the pure essence of academic scholarship. But the truth was that I was driven by straight-up fear: I was afraid of not being able to graduate within a reasonable time frame, so I pressured myself to come up with new ideas that could potentially lead to publications.

In theory, technical papers should be judged on their merit alone, but in reality, reviewers each have their own unique subjective tastes and philosophical biases.

I programmed day and night, often dreaming in my sleep about the intricate details that my code had to wrestle with. Every morning, I would wake up and jump straight to programming, feeling scared that this would finally be the day when I hit an insurmountable obstacle proving that it was.

My fear, though, was that I was already exhausted from my past year of super-grinding and had no new project ideas brewing.

Grant reviewers will likely be even less sympathetic since they are the gatekeepers to millions of dollars and would rather hand the money to colleagues who are doing more mainstream types of computer science research.

One of the claimed benefits of academia is the allure of creative freedom, but my decision to leave academia actually freed up my mind to become even more creative in pursuing my true professional passions.

The popular view of how a Ph.D. dissertation arises is that a student comes up with some inspired intellectual idea in a brilliant flash of insight and then spends a few years writing a giant treatise while sipping hundreds of lattes and cappuccinos. In many science and engineering fields, this perception is totally inaccurate: The “writing” is simply combining one’s published papers together into a single document and surrounding their contents with introductory and concluding chapters. All of the years of sweaty labor has already been done by the time a student sits down to “write” their dissertation document. In my department, the most important milestone in a Ph.D. student’s career is when their advisor gives the thumbs up to begin the dissertation writing process. This gesture signals that the student has done enough work—usually publishing two to four conference papers on one coherent theme—and deserves to graduate within a few months.

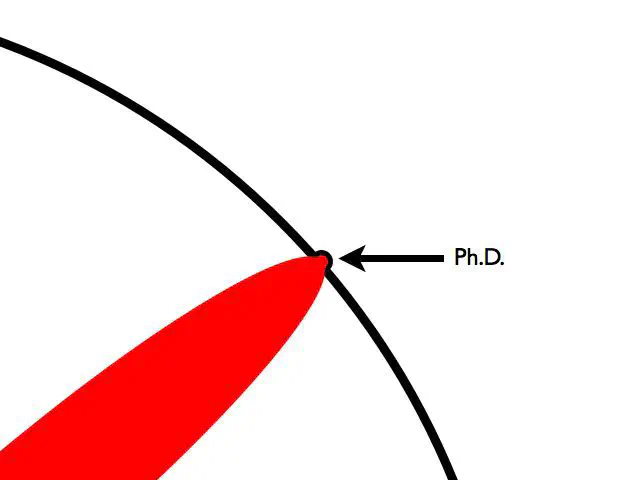

In the end, like most Ph.D. dissertations, mine expanded the boundaries of human knowledge by a teeny microscopic amount. The five prototype tools that I built contain some interesting ideas that can be adapted by future researchers. In fact, I will be honored if future researchers cite my papers as examples of shoddy primitive hacks and argue for why their techniques are far superior. That’s how research marches forward bit by bit: Each successive generation builds upon the ideas of the previous one.

It’s been a long, circuitous, and unpredictable journey, but I’m incredibly grateful that I was able to turn this broad topic—one out of dozens that caught my interest over the years—into my Ph.D. dissertation.

If you are not going to become a professor, then why even bother pur-suing a Ph.D.? This frequently-asked question is important because most Ph.D. graduates aren’t able to get the same jobs as their univer-sity mentors and role models—tenure-track professors. There simply aren’t enough available faculty positions, so most Ph.D. students are directly training for a job that they will never get. (Imagine how dis-concerting it would be if medical or law school graduates couldn’t get jobs as doctors or lawyers, respectively.)

So why would anyone spend six or more years doing a Ph.D. when they aren’t going to become professors? Everyone has different mo-tivations, but one possible answer is that a Ph.D. program provides a safe environment for certain types of people to push themselves far beyond their mental limits and then emerge stronger as a result. For example, my six years of Ph.D. training have made me wiser, savvier, grittier, and more steely, focused, creative, eloquent, perceptive, and professionally effective than I was as a fresh college graduate. (Two ob-vious caveats: Not every Ph.D. student received these benefits—many grew jaded and burned-out from their struggles. Also, lots of people cultivate these positive traits without going through a Ph.D. program.)

Here is an imperfect analogy: Why would anyone spend years train-ing to excel in a sport such as the Ironman Triathlon—a grueling race consisting of a 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bike ride, and a 26.2-mile run—when they aren’t going to become professional athletes? In short, this experience pushes people far beyond their physical limits and en-ables them to emerge stronger as a result. In some ways, doing a Ph.D. is the intellectual equivalent of intense athletic training.

I’ll end by answering a question involving the F-word: Was it fun?

Some aspects of the Ph.D. experience were very fun: Coming up with new ideas was fun; sketching out software designs on the white-board was fun; having coffee with colleagues to chat about ideas was fun; hanging out with interesting people at conferences was fun; giving talks and inciting animated discussions was fun; receiving enthusias-tic emails from CDE users around the world was fun. But I probably spent only a few hundred hours on those activities throughout the past six years, which was less than five percent of my total work time.

In contrast, I spent about ten thousand hours grinding alone in front of my computer—programming, debugging, running experiments, wrestling with software tools, finding relevant information, and writ-ing, editing, and rewriting research papers. Anyone who has done creative work knows that the day-to-day grind is rarely fun: It re-quires intense focus, rigorous discipline, keen attention to detail, high pain tolerance, and an obsessive desire to produce great work.

So, Was it fun?

I’ll answer using another F-word: It was fun at times, but more importantly, it was fulfilling. Fun is often frivolous, ephemeral, and easy to obtain, but true fulfillment comes only after overcoming significant and meaningful challenges. Pursuing a Ph.D. has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my life, and I feel extremely lucky to have been given the opportunity to be creative during this time.